About halfway into The Physics of NASCAR: How to Make Steel + Gas + Rubber = Speed, Larry McReynolds describes a race car as "a science experiment."

The former crew chief nailed what's most compelling about physicist Dr. Diandra Leslie-Pelecky's scientific deep-dive into NASCAR. During a race weekend, teams must capture data on, make sense of, and ultimately correctly adjust thousands of complex variables on a car. The author ultimately succeeds in the unenviable task of making this unfolding science experiment interesting to the reader.

Each NASCAR team's battles in the ongoing war against continuing critical balances -- in tire pressure, myriad chassis adjustments, aerodynamics, even how much a driver ca n safely perspire -- comes through most vividly as Leslie-Pelecky observes Elliott Sadler's No. 19 team from the pits at several races last season.

n safely perspire -- comes through most vividly as Leslie-Pelecky observes Elliott Sadler's No. 19 team from the pits at several races last season.

I won't give away the ending. Let's just say the driver from Virginia exhibits grace and charm amid significant challenges.

Leslie-Pelecky, a physics professor at the University of Texas, is an inquisitive scientist packing a novelist's eye -- and nose. Walking into a race shop for the first time, she notes a "characteristic aroma." She later learns it's a mixture of brake cleaner and gear oil.

Common fan experiences, like the traditional pre-race flyover, become a data-rich science lesson: "The planes are never where you expect them to be when you look up because light waves travel about a million times faster than sound waves."

An explanation of car paint schemes (which today are mostly decal wraps) gloriously detours into cow farts (the smell of a unique chemical in automotive paints), and why the Wood Brothers employ a removable decal wrap on the Little Debbie car (sponsor executives, who are Seventh Day Adventists, don't conduct business on Saturdays, which includes NASCAR practice).

Teams use lighter oil during qualifying. Right side tires are bigger than left side tires. NASCAR windshields are made from the same plastic as you iPod screen. Lug nuts are painted florescent pink because that's the most jarring color to the human eye.

Do we really need to know all this? Well, if you are a NASCAR fan, yes -- you do!

More substantively, Leslie-Pelecky brings readers inside many off-limits places: the fabrication department at Hendrick Motorsports; the No. 19 hauler at Atlanta Motor Speedway; the shop floor at Roush Fenway Racing; a crash test in Lincoln, Neb.; and the NASCAR Research & Development Center.

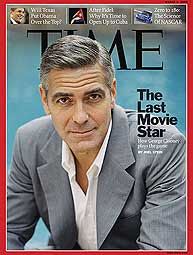

Dr. Diandra Leslie-Pelecky's scientific deep-dive into NASCAR is profiled in this week's TIME magazine.

Leslie-Pelecky likes explaining things. Some are endemic to NASCAR, like how engines, brakes, shocks and springs work, and why torque is as important as horsepower in producing speed.

Her tangential points are the most fun. In explaining the sport's safety advances, she detours into the story of a spider silk handkerchief stopping a bullet in a gunfight. The author's cheery tone keeps her liberally sprinkled esoteric references away from intellectual show off-ism. The drivers start their engines, and the wide-eyed physicist inserts her ear plugs. She can't help but note that chickens and sharks can grow back the hair cells that loud noises damage, but humans cannot.

In simple language, with sometimes funny descriptions, Leslie-Pelecky explains track and sway bars, wedge, and tire camber, how a "toed-in" car looks and handles.

It may seem downright bizarre to explain oil viscosity by comparing engine oil flow to Dale Earnhardt Jr. dodging media in a crowded garage, but she makes it work.

The Physics of NASCAR is an "idiot's guide" for those of us who have watched too many races to be dummies.

Consider this book required curriculum in our sport for anyone who wants to work in NASCAR, announce a race, or simply be the smartest NASCAR fan in the room.

The former crew chief nailed what's most compelling about physicist Dr. Diandra Leslie-Pelecky's scientific deep-dive into NASCAR. During a race weekend, teams must capture data on, make sense of, and ultimately correctly adjust thousands of complex variables on a car. The author ultimately succeeds in the unenviable task of making this unfolding science experiment interesting to the reader.

Each NASCAR team's battles in the ongoing war against continuing critical balances -- in tire pressure, myriad chassis adjustments, aerodynamics, even how much a driver ca

n safely perspire -- comes through most vividly as Leslie-Pelecky observes Elliott Sadler's No. 19 team from the pits at several races last season.

n safely perspire -- comes through most vividly as Leslie-Pelecky observes Elliott Sadler's No. 19 team from the pits at several races last season.I won't give away the ending. Let's just say the driver from Virginia exhibits grace and charm amid significant challenges.

Leslie-Pelecky, a physics professor at the University of Texas, is an inquisitive scientist packing a novelist's eye -- and nose. Walking into a race shop for the first time, she notes a "characteristic aroma." She later learns it's a mixture of brake cleaner and gear oil.

Common fan experiences, like the traditional pre-race flyover, become a data-rich science lesson: "The planes are never where you expect them to be when you look up because light waves travel about a million times faster than sound waves."

An explanation of car paint schemes (which today are mostly decal wraps) gloriously detours into cow farts (the smell of a unique chemical in automotive paints), and why the Wood Brothers employ a removable decal wrap on the Little Debbie car (sponsor executives, who are Seventh Day Adventists, don't conduct business on Saturdays, which includes NASCAR practice).

Teams use lighter oil during qualifying. Right side tires are bigger than left side tires. NASCAR windshields are made from the same plastic as you iPod screen. Lug nuts are painted florescent pink because that's the most jarring color to the human eye.

Do we really need to know all this? Well, if you are a NASCAR fan, yes -- you do!

More substantively, Leslie-Pelecky brings readers inside many off-limits places: the fabrication department at Hendrick Motorsports; the No. 19 hauler at Atlanta Motor Speedway; the shop floor at Roush Fenway Racing; a crash test in Lincoln, Neb.; and the NASCAR Research & Development Center.

Dr. Diandra Leslie-Pelecky's scientific deep-dive into NASCAR is profiled in this week's TIME magazine.

Leslie-Pelecky likes explaining things. Some are endemic to NASCAR, like how engines, brakes, shocks and springs work, and why torque is as important as horsepower in producing speed.

Her tangential points are the most fun. In explaining the sport's safety advances, she detours into the story of a spider silk handkerchief stopping a bullet in a gunfight. The author's cheery tone keeps her liberally sprinkled esoteric references away from intellectual show off-ism. The drivers start their engines, and the wide-eyed physicist inserts her ear plugs. She can't help but note that chickens and sharks can grow back the hair cells that loud noises damage, but humans cannot.

In simple language, with sometimes funny descriptions, Leslie-Pelecky explains track and sway bars, wedge, and tire camber, how a "toed-in" car looks and handles.

It may seem downright bizarre to explain oil viscosity by comparing engine oil flow to Dale Earnhardt Jr. dodging media in a crowded garage, but she makes it work.

The Physics of NASCAR is an "idiot's guide" for those of us who have watched too many races to be dummies.

Consider this book required curriculum in our sport for anyone who wants to work in NASCAR, announce a race, or simply be the smartest NASCAR fan in the room.

No comments:

Post a Comment